This is my final post for

The Diary of an Intimate Stranger from Colombia, this year, I am closing with a story, instead of my habitual use of photography. It's a story about Colombia and my final chapter at

El Tiempo. It's some Christmas reading fun about being a foreigner at Colombia’s largest newspaper.

By Richard Emblin

Recently some friends of mine hosted a farewell dinner for me in a fancy apartment in the hills surrounding Bogotá. It was their way of saying thank you for having endured six years at El Tiempo- Colombia’s largest paper- and strangely enough 'congratulate' me for moving on. And it put a savoury end to my time as a foreign Photo Editor, working in this South American country. But when I told them my impressions of Colombia and eating habits, I had a dozen of this country’s most respected journalists and editors literally choking to death, on chicken salad. So I thought, that for those of you, who identify Colombia with cocaine and drug traffickers, that I would break it to you gently and say, that there is another, much graver threat coming out of Colombia these days, to our public health system and if I manage to finish this article, Colombia’s tarnished image with drugs might be replaced by, pork-rinds. That’s right, the dreaded chicharron. The chi-cha-what?. The chi-cha-ron.

Now in Colombia, every self-respecting household consumes large quantities of chicharron. It’s very popular and served with virtually, every meal. Especially in the peaceful and hardworking city of Medellin, where the local dish consists of fried plantain, red beans, rice and you guessed it, pork-rinds. The people of Medellin, are known as paisas, and are big on colonization. They gave the world cocaine- thanks to their local bad boy made good- Pablo Escobar- and they have managed to successfully bombard Colombia with pork-rinds. Little chunks of pork, deep fried in grease so that the cholesterol level rises by about 400 percent and then these crispy nuggets are left out to dry for a few days, preferably, by the side of a road, under the hot tropical sun.

Now, sometimes if you are lucky, you can find a chicharon with pig-hairs sticking out of them. Imagine that. What a treat. And yes, the rule of thumb is, the greasier the chicharon, the better.

Popular legend has it that pork-rinds were a late addition to the local dish of Antioquia - the state which Medellin is the capital of - and the name, Antioquia, originally comes from Antioch, thanks to the first Jewish settlers who came to this remote corner of the world- originally came from Spain - during the Inquisition, which started burning people back in the fourteenth century. Antioquia, was named after the motherland- the holy land- and rather than be tortured, several galleons of exiled Jews, ran ashore off the coast of Colombia, and as these brave refugees, headed inland they used local ingredients to cook and arrange their food in a similar fashion, as they had done so back in the old country. So on a typical Colombian plate – the bandeja paisa- the rice is kept separate from the beans, and the beans separate from the plantain and no one after fifteen years in this country, has given be a verifiable explanation as to how the pork-rind nuzzled its way on to Colombia’s national dish.

So when I joined El TIEMPO back in 2000, as one of only a handful of foreigners to work in this established Colombian newspaper- not teaching English as a foreign language to journalists- I was told that on Fridays’ the cafeteria served bandeja paisa. Great - I thought- what better way than to close a newspaper at night with a belly full of beans, plantain and pork-rinds. This tradition will never change, along as El Tiempo continues to print, and after ninety-something years, Fridays, is still pork-rind day and should stay that way for another century.

I could go back to El TIEMPO- not that I really want to- and still find that on any given Friday, there are pork-rinds being served in the cafeteria to 3000 employees. Now there is dark side to this story -if not I wouldn’t be writing this letter from Colombia- and it has nothing to do with my permanent state of indigestion. It has to do with the fact that over the years, the chicharon has become synonymous in this country with having ‘a problem’ and everything that can go wrong and does often, in Colombia, is endearingly referred to as a ‘chicharon’. The bigger the pork-rind, the graver the problem. If your bank statement got lost, you have a chicharon. If you car was unjustly towed –you guessed it- you had another chicharon. In actual fact, living in Colombia can be so complex and difficult at times, that it presents so many pork-rinds on an average working day.

To get things done in this country, you have to have an appetite for living dangerously, and as I was soon to learn - the hard way –working at EL TIEMPO was no exception. You could be sitting at your computer terminal, when all of a sudden, a journalist would shout at the top of his voice -Que chicharon!- what a mess- and your concentration would be shattered by jelling and screaming. No, it wasn’t a car bomb that just exploded, or another massacre involving the left wing rebels of the FARC - in which the death count when less than fourty. (which meant that it didn’t even make a footnore in the paper ) it was just the fact, that someone’s article about corruption in the Bogotá city council had gotten erased from the editorial system known fondly as Herpes - sorry Hermes 10 point something or other, and everyone in the newsroom, had to know about your latest pork-rind.

As Photo Editor at El TIEMPO, I had my fair share of pork to grind. My daily chicharron. And my photographers saw to it that I was well supllied. Cameras would disappear on a regular basis -not surprising in a city with the crime rate high as Bogotá- but it meant having to fill in vast amounts of paperwork and putting one’s life on hold, never mind everyone else’s, while I was fingerprinted by the National Police and the Attorney General’s office. Every time there was a major news event, breaking out somewhere in the world, which is quite common when you work at a newspaper, my best picture of the day would somehow, mysteriously vanish from my computer. This invariably happened at four o’clock, during the most pressing and stressful deadline. I don’t know where all these pictures are or went, but somewhere out there in cyberspace is a photo graveyard with wonderful photos from Afghanistan, Iraq and Colombia.

“Does anyone know what happened to the picture of Arafat’s funeral?, I would ask my colleagues when an AP photo would all of a sudden vanish from my screen. “You know, the one where Arafat’s coffin is being unloaded by crowds of chanting Palestinians?. Blank stares. The picture that just came in from Gaza?. More empty stares. ‘Does anyone know where Gaza is ?. Silence. Arafat?. Nothing?”. I just wanted to recuperate the picture with the helicopter in it. It’s not too much to ask. So, in desperation I would lift up the speakerphone and implore across the newsroom: “Foreigner 8256 actually employed as your Photo Editor, sitting at desk 15, near the northeast corner window, urgently requests assistance from Systems department to locate picture of Arafat with a helicopter’. “It’s me- senor Emblin- your gringo photo editor”. Invariably the nice fellows from the IT department never came. I guess they wanted me- the outsider- to boil in my own juice, or better still, grease.

Now Colombians are decent, hardworking and more often than not, friendly people- unless of course you have 'pork to grind' with your bosses- and I have never felt resentment towards me in this country for being an extranjero- foreigner- and I have always tried to be a law abiding resident trying hard not to step on anyone’s feet or hooves. So when I headed down to cafeteria at EL TIEMPO years ago on a rainy Friday, around lunchtime, I was anxiously awaited my first official meal of the legendary ‘paisa’ platter. I picked up my tray, waited in line, as secretaries -one by one- and line operators from the printing press- picked out their plantains and pork-rinds. There didn’t seem to be a problem with this set up for handing out the chicharon, and regardless of rank or file, EL TIEMPO seemed like a very democratic place to work. Everyone in the company is allowed one- not two- toasted and crispy chicharon. So, if you wanted more beans, the ladies in the cafeteria simply handed you a smaller ‘problem’ and I might add, added years to your health and life.

As I had only been in the company for a few days, it didn’t take long for everyone to know that the gringo had arrived in EL TIEMPO. Word was out that I had entered the hallowed halls of this publishing empire owned by the Santos family. Now the Santos- name which means ‘Saints’ in English- are everywhere, except of course in the cafeteria. There are Saints in government- the actual vice-president Francisco is one- and there are Saints in every important position in this South American democracy. They are Colombia’s royal family and 'Buckingham palace' is a large brick bunker on the western fringes of Bogotá, known as the CEET, pronounced: se'at, as in 'seat of power' or ceet of discomfort ?. Now, the Santos not only run Colombia’s national newspaper, but they run everything else in between. And don't expect receiving an email from the Emperor himself, (far from a saint) as he don't communicate with serfs. Like die-hard Colombians they too enjoy pork-rinds, and god forbid, falling out with The Saints means, no more greasy nuggets, for you !!!.

So what was the problem for a Canadian journalist like myself actually wanting a hot, decent meal at work?. I didn’t think there was one, until I was involved in a chicharon saga. As I approached the lady in her white overalls serving behind the glass counter in the basement cafeteria, I knew my moment to be accepted at this newspaper had arrived. Suddenly, as I came face to face with her, I muttered in my broken Spanish, the customary words ‘Buenos dias, senorita…I’ll have the paisa platter, por favor’.

‘With beans’ came a sharp reply. ‘Yes, please’. ‘Rice?’. “Yes” I answered obediently. “Plantain?” “How nice” I begged with a radiant smile. ‘Chicharon?. “Of course’ I said enthusiastically. Then, she thrust her metal prongs into a large shiny bowl and began searching for what was about to become a massive problem for her, for me and my life in the house of Saints.

She produced the evidence - the smallest chicharon ever fried in the history of Colombia- and placed in on my plate. I looked at the burnt kernel of disgrace, and looked again. ‘Excuse me Miss, I this what you call a chicharon?, I enquired, shocked and dismayed. ‘Yes’ she replied, in a rather sharp tone of voice, and yelled ‘Next’. ‘But, it looks awfully small to me”, I said. ‘Take it or leave it” she rebutted, frowned and nodded at the next person in line, who seemed to have a generous portion of everything, including not one, but two pork-rinds. In actual fact, everyone had wonderfully large portions of everything. Why did she give me the smallest, most miserable piece of grizzle?. Dejected, I grabbed my 300 grams of potato soup, to accompany 36 red beans, 445 grains of rice, two yellow plantain sticks and headed off to find a table.

Now, I am someone who doesn’t complain about things, let alone the size of my chicharon, but I was so upset that as I spoke with an accent, looked like a foreigner in this country, that the hostess had made an arbitrary decision to cut back on my lunch rations, that I wrapped my kernel in a paper napkin, and decided to confront the situation from behind my desk in the newsroom with a polite letter to the General manager of the EL TIEMPO kitchen service. “Dear Sir, this afternoon - began the letter- while I was happily, expecting to be served the greatest of all dishes, the bandeja pasia, I came upon this most uncomfortable situation…

Now, I will not go over the letter in detail, except to say, that it was well intentioned and cordial. I felt it my duty as a foreigner working in the Colombian newspaper to have the right to complain about what, I believe, what some strange form of discrimination?. I had been forced to the back of the lunch bus for being a gringo and I was going to stay there for many years- as I later found out- for not speaking properly. Now for those foreigners who want to work in a Colombian company, my heart goes out to you, and my recommendation is, bring a box lunch.

Needless to say, the chicharon problem, created a huge problem El Tiempo. Within minutes, I had the entire catering department, leering at me with sullen faces. “Senor Emblin, what was the problem? said the affable manager. ‘Well funny you should ask… let me show you” I responded, as I popped the greasy tid-bit from my jacket pocket and placed it on my desk. “Does this look like a chicharon, to you?’. There was silence, shock and outrage. “No, no, definetly, not, senor. We don’t serve those types of chicharon here” he proclaimed. ‘Well, Sir, I don’t want to create a scene, but I really do like Colombia, and as a foreigner, I actually do like Colombian food, so it would be nice if in the future, I received a pork-rind on my plate, just like everyone else”. Sensing tension and nervousness in the newsroom, I surrendered gracefully and decided not to question corporate pork-rind polices again.

I endured my years in EL TIEMPO, facing many bouts of upset tummy on Fridays and one too many massacres. During 270 pork-rind days, I never received a decent portion, and I feel a happier and healthier person as a result. It was only until last month, when word got out -again- in the house of the Saints- that the gringo was being let go, that I stood in line at the cafeteria and asked the catering lady for my last ‘bandeja paisa’. Reaching in the silver bowl with her metal prongs, she produced the biggest, fatest chicharon there was, and plonked it on my plate. ‘Gracias’ I said, realizing that it took six years for me to get to this point where my portion was actually the same size, as everyone else’s. That was the least of my problems, on the last day of work as I had resolved my porkrind issue with the newspaper, and now I had to face the bean counters.

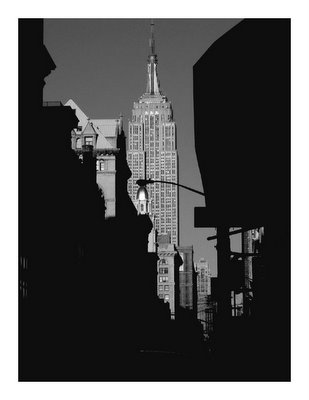

First walk down Prince Street, 1989.

First walk down Prince Street, 1989.