Thank you to all of you who have read and will continue read this blog. I know many of you have been worried about me during the last eight months, since I left my job at the newspaper of Mr. Pompus & Saints (El Tiempo). Yes it has been hard. Hard on my mind and the bank account, of course, but never on what has true value: the soul. So life threw me into a whirlpool of emotions and self doubt, risk and few rewards. But the journey so far has been worth the struggle. It always is at the end. Especially when one is fortunate to have friends - many of whom I've never met- like you. Thanks for the endearing comments and words of support on this weblog and for being part of the adventure and the stories.

Thank you to all of you who have read and will continue read this blog. I know many of you have been worried about me during the last eight months, since I left my job at the newspaper of Mr. Pompus & Saints (El Tiempo). Yes it has been hard. Hard on my mind and the bank account, of course, but never on what has true value: the soul. So life threw me into a whirlpool of emotions and self doubt, risk and few rewards. But the journey so far has been worth the struggle. It always is at the end. Especially when one is fortunate to have friends - many of whom I've never met- like you. Thanks for the endearing comments and words of support on this weblog and for being part of the adventure and the stories.

Friday, June 30, 2006

Thank you to all of you who have read and will continue read this blog. I know many of you have been worried about me during the last eight months, since I left my job at the newspaper of Mr. Pompus & Saints (El Tiempo). Yes it has been hard. Hard on my mind and the bank account, of course, but never on what has true value: the soul. So life threw me into a whirlpool of emotions and self doubt, risk and few rewards. But the journey so far has been worth the struggle. It always is at the end. Especially when one is fortunate to have friends - many of whom I've never met- like you. Thanks for the endearing comments and words of support on this weblog and for being part of the adventure and the stories.

Thank you to all of you who have read and will continue read this blog. I know many of you have been worried about me during the last eight months, since I left my job at the newspaper of Mr. Pompus & Saints (El Tiempo). Yes it has been hard. Hard on my mind and the bank account, of course, but never on what has true value: the soul. So life threw me into a whirlpool of emotions and self doubt, risk and few rewards. But the journey so far has been worth the struggle. It always is at the end. Especially when one is fortunate to have friends - many of whom I've never met- like you. Thanks for the endearing comments and words of support on this weblog and for being part of the adventure and the stories.

Monday, June 26, 2006

ABNEY PARK

We met among the dead

stomping cigarette ends into earth,

moist and bleached by summer’s past warmth

and now, the chill of gritty tombs and twisted steel

are a foundation for a drama,

with scenes of birth

death and kitchensink

liebestraum.

I unlatch secrets,

words bolted together to form meaning

amids meaningless ritual.

I get coffee. It is cold.

Cold as grave ground death talk

where love was a cue

onto some dark stage

with trees bare and chaste

shedding insecurities

with dour leaves and soiling memory.

Here among the stone angels,

kneeling in prayer my soul fattens

like an ivory Buddah until

the ivy chokes and swallows them

to be lost forever in peace, fragments

in a chain, linking my death

with our common desire for

myth and understanding.

Abney Park. Hackney, London. 1990

Saturday, June 24, 2006

I have looked at days

I have nothing left to say

I have looked at days gone grey,

and wondered how happiness

was led astray by some heart

too heartless to mistake

my love for lust.

Oranges and lemons say the bells of St.Clements

Walking through my memories

as the sun begins to fade

I listen to the rumours

my empty world has made.

tokio

My life has been in honour of your name

but you didn't feel the same,

so I have nothing left to say

I have looked at days gone grey

and wondered how happiness

was led astray by some heart

too heartless to mistake

my love for lust.

Oranges and lemons say the bells of St.Clements

Walking through my memories

as the sun begins to fade

I listen to the rumours

my empty world has made.

tokio

My life has been in honour of your name

but you didn't feel the same,

so I have nothing left to say

I have looked at days gone grey

Wednesday, June 14, 2006

I first laid eyes on her at the Hotel Amazonia in downtown Cayenne. Her tanned, pint-sized breasts heaved towards the sky like the boosters of an Ariane rocket. The dingy excuse of a pool had become a catwalk of men, trying to catch her attention by pointing their speedos towards her, like wind socks on a launch pad. But it didn’t take a rocket scientist from the European Space Agency to discover the real identity of this mysterious brunette. I did.

Haggling with the concierge, I was told that the exhibionist was none other than the incredibly talented porn star known as Julia Channel. ‘It’s Julia. Le star du equis ’, whispered Francoise, as he arranged room keys at the reception. I had hardly touched down in this outpost of French colonialism in South America, and I was within striking distance of my introduction into the French film industry. Who needs Cannes I thought, when you can have Cayenne?.

It was evident from my arrival that French Guiane was an outpost for the misunderstood - rocket scientists, Legionnaires, a porn star on the literary trail of ‘Papillon’. I had watched back in my college days, many late night reruns of the movie ‘Papillon’ starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman, so I was drawn to French Guiane, not out of lust for Julia, but wanderlust. This small territory of France, wedged between Suriname in the west and the northeast shoulder of Brazil, is home to another breed of outcasts made famous in the movies - the French Foreign Legion.

From my home in Bogotá – Colombia - the trip involved three time zones, a night in Caracas, and a milk run of stopovers in the French Caribbean islands. When the Air France shuttle finally touched down at the Rochambeau Airport, -a gleaming terminal just outside the capital Cayenne - my travelling companion and I entered into shock. We could not believe that we were still in South America. Instead of the mud huts, we have grown accustomed to seeing from foggy aircraft windows, we had arrived at ‘de Gaulle’ of the Amazon.

And French Guiana is a department of France stubbornly resisting assimilation with the rest of the continent. At customs, a brusque grammar-Nazi scrutinized my faulty French pronunciation, but ignored my luggage. There are no roads to Brazil, but passengers fly direct to Paris on Air France. The currency is the French franc and the TV is beamed in from the Old World. The centrepiece of our hotel was a polished porcelain bidet.

After doing the tourist walk through Cayenne’s palm-lined Place des Palmistes, I faced the daunting prospect of finding souvenirs to take back home. I knew that once I left this tin roofed city in search of the abandoned prison camps, I would be as Papillon said ‘out in the middle of the swamp 1,000 miles from nowhere’. But the local shops sold mostly boxed butterflies- giant blue monarchs- and expensive French lingerie. I settled on a winged bug.

With my dictionary in one hand, and my endangered species in the other, I headed to the state museum to stock up on my general culture of the Guiane. The Caribbean-style mansion of painted wooden beams which housed the Museum seemed to be one of the few buildings in Cayenne which was not shuttered up on a rainy afternoon. After paying the entry fee of 20 francs, I wandered around giant jars of jaundiced formaldehyde with the preserved remains of snakes and floating toads. But on the second floor of the old Musee, a small cabinet caught my attention.

The cabinet formed part of an exhibition called- Les Briques du Bagne- the bricks of the ‘Bagne’. Three clay bricks, engraved with the letters A.P. stood on display. The bricks seemed somehow special and important to occupy such a privileged corner of the Museum. I had grown accustomed to museums all over South America which display canon balls and Simon Bolivar’s extensive collection of swords. But these bricks obviously played an important part as building blocks in this territory’s history.

In my faulty French, I asked the curator why the bricks?. He looked dumbfounded. I was the only tourist in three hundred years to take the effort of visiting the museum in Cayenne, and I was thrust into linguistic gridlock. I tried again. ‘Why the bricks?’. Why would a museum display three - one hundred year old - bricks?. ‘These are the bricks made by the prisoners of the Bagne’, came the reply.

WhenI stepped out of the museum, I was culturally enriched, but felt scolded. I had been in the Bagne all along. Bagne being the word used to describe this mosquito infested swamp and the land used by the old penal system operating across the territory. It was then that an awful thought crossed my mind. I must find a brick. Who needs a butterfly carcass when you can have a brick?. My motive was set, all I needed to do was find one.

In the eighteenth century, France was at war, fighting for control of her newly conquered territories in Canada and Louisiana from her arch-rival, the British. France also wanted to snag a piece of the colonial action in South America and in 1642 claimed the dense rainforest of the Guiane, as theirs. But serving no real economic purpose to Versailles, an edict was passed in 1791, converting the Guiane as a deportation centre for a cumbersome prison population who would subsequently died of yellow fever and malaria. As the French colonial experience in South America failed, another idea took root in France. Three tiny islands perched 40 kilometres from the Guianese shore were to become an experimental Alcatraz in the Atlantic.

This leafy cluster of islands, ironically called the Iles du Salud -Islands of Health- housed its first political prisoners back in 1792. But the exercise in convict deployment was short lived. Domestic problems at home forced the French Government to abandon the prisons and for decades the inmates languished on a forgotten shore. Following the successful deployment of criminals from England to Australia in the nineteenth century, France decided to follow example and populate the Guiane as one giant concentration camp.

A decree in 1852, set the process of mass deportations and common criminals were carted off to serve their sentences overseas in the sunny Caribbean. During the first couple of years some 8000 criminals were shipped here, but only 3000 survived. Poor hygiene and raging epidemics wrecked havoc on the inmates and the islands became identified with death and despair, instead of good health.

As the penal system grew, so did its reputation. It was impossible for convicts to escape from these islands, due to the shark infested waters, rough currents and treacherous cliffs of wind beaten rock. Soon these remote islands earned the nickname the ‘Devil’s Islands’, because they housed the most dangerous criminals of the Republic. In order to populate the islands, the French penal administration set up camps on the mainland and put petty criminals to work clearing the rainforest and cultivating the land. This system of work labour became known as ‘doublage’, or double- time. For every year, a prisoner spent locked up in confinement, he had to do an equal amount of time in the swampy ‘Bagne’ cutting down trees and cooking clay bricks to build more prison cells.

As France rushed to populate the Guyane, many prisoners were, in fact innocent of their crimes. Hasty trails and false accusations resulted in a series of scandals for the French government, in which respectable men were deported to this tropical inferno and left to die. Such was the case of Alfred Dreyfus, who became the cause célebre of the French intellectual classes and who insisted on his innocence, despite the fact that a military tribunal had accused Dreyfus of high treason for supposedly selling military secrets to the Prussian army. As a high ranking coronel in the French Army, Alfred Dreyfus was deported to Devil’s Island and spent four years and three months trying to get an appeal. It was only after the influential author and human rights crusader, Emile Zola wrote a dissertation titled ‘J’accuse’ in defence of Dreyfus that the French people realized the real motives behind Dreyfus’ arrest and exile.

The son of a Jewish family, Dreyfus had been framed by anti-Semites in the French establishment. Although Dreyfus regained his freedom in 1889, his military career was over and his reputation damaged beyond repair. Even today, a century after Dreyfus’ release, the so-called Dreyfus Affair continues to haunt the French political scene.

Although much of the infamy of the Devil’s islands is attributed to this famous political prisoner, the fate of others here is largely forgotten. Only one documented escape was pulled off my Charles de Rudio, who was dispached to the islands for his assasination attempt against Emperor Napoleon III of France. A plaque in the old warden’s residence, commemorates the legacy of the less fortunate inmates.

Today, the islands are an attraction for curiosity seekers from Europe who endure the hour’s boat ride from Cayenne. The forty kilometers trip could be easily done, if the sea is calm, but the crossing is at best of times, rough. Passengers are warned from the start to find seats inside the catamaran built for hurricane force winds. But I wanted to be out on desk, with the typical French honeymooners and of course, Julia in her white tank tee and Gucci glasses. Julia was on a sabbatical from the big screen. Too much porn, I guess can drive you to French Guiane.

Yet despite the waves, and being exposed to the best wet t-shirt contest of my life, Julia and I disembarked at the largest of the islands of the ile Royale. It’s funny what a hundred years can do to a place like Devils’ Island - a porn star and a photographer strolling down the concrete pier where once emaciated prisoners did.

The ile Royale, was the main penal colony, and housed most of the criminals, including Dreyfus and ‘Papillon’. Coconuts lie strewn across narrow foot paths, leading up a crumbling cemetery and down to a lighthouse tower and some abandoned barracks. After fifty years, nature has taken over some of the buildings transforming the cell blocks into eerie heaps of rubble and twisted steel. The solitary confinement cells still remain, but the roofs have caved in by erosion and the permanent pounding of hurricanes and tropical storms. But traces of penal life are strewn everywhere, literally. The wooden doors which once were slammed shut in the face of a convict, hang on their rusty hinges and one can count the scratches on a walls where a prisoner counted his days in darkness.

I climbed into an abandoned cell and closed the thick wooden door on myself. The shrill of the chicaras and the crying of black crows in the trees faded with the solitary confinement. The world around me fell silent. I was in what Charriere called the ‘mangeuse d’hommes’- the eater of men. Meanwhile Julia was strolling down by the sea - scouting for locations for her upcoming epic, and dipping her feet in the sea.

Convicted in Paris in 1931, at the age of twenty-five, for a murder he supposedly did not commit, Henri Charriere’s legend haunts Devil’s Island. Forty two days after his arrival in the French penal colony, Charriere became known as ‘Papillon’ because of the giant blue butterfly tattooed on his chest. He managed to escape, traveling some 1500 miles on the open sea in a tiny boat, but was recaptured by the French authorities and sentenced to two years in solitary. After seven more daring yet unsuccessful escapes, he was banished to Devil’s Island, in this archipelago of the damned. Finally, after languishing on the same island where Alfred Dreyfus pondered his fate, Papillon tried escaping one last time, by calculating the ebb and flow of tides, wind currents and the presence of sharks. The butterfly then floated to freedom on a raft made out of abandoned coconuts shells.

However most ‘bagnards’ – convicts - were not as lucky as Papillon. Prison terms handed down to the deportees were no less than ten years, and subsequently the convicts had to remain in French Guiana at least twenty. With the great influx of convicts, towns flourished and were administered entirely by the A.P.- the Administration Penitentiare. In St. Laurent de Maroni, an Indian community was displaced to make way room for a sprawling prison compound and the notorious Camp de Transportation. Here, prisoners who had survived the two week transatlantic crossing were processed and housed until their legal situation was defined. Most were banished to the islands, others were forced into chain gangs, clearing the forest and dying of hunger and infection. However, the most famous inmate of the Camp de Transportation has still not been released.

Locked in a wooden crate, in a building dilapidated by hanging vines and shrubs, the guillotine which once served the A.P, has been forgotten by the passing of time. Hundreds of men were executed in St. Laurent de Maroni, as a public display of terror and their cadavers thrown into the forest nearby. Execution by guillotine continued until the camp’s closure in 1936. For the prisoners who did not die by the blow of the blade, a lifetime in the bagne did not prove any better. The bagne became known as the ‘guillotine seche’ or dry guillotine, because it led to a slow, certain death in the tropics. Of the 70,000 convicts sent to French Guiana only 20,000 men survived.

Often, the prisoners who were swiftly executed by the guillotine, were considered the lucky ones. Being banished to the bagne, meant that, you lost touch with your family, and you could spend your entire life, going in and out of solitary confinement, sometimes not seeing the light of day, for years at a time. After being locked up in total darkness and isolation, the psychological scars ran deep. When the Salvation Army stepped in to help repatriate thousands of prisoners from 1946 to 1953, many men had no where to go. France begrudgingly had to received the bagnards, but French society did not.

By the time, a freed man returned home, there was often no trace of the life he once lived. Entire families had moved on or loved ones perished in the world wars which ravaged Europe during the ‘bagne’s’ existence. Some prisoners, after only having known the world inside the cold, damp walls of their cells, stayed on in the Guiane after liberation. Most notably, prisoners from France’s other colonies, Algeria and Morocco, who never really considered France as their home, found themselves spending their final days to this remote corner of the world.

For many ex convicts, the process of reintegrating back into society was as traumatic as the life they led behind bars. For the men who had been educated in France as skilled labourers, carpenters and blacksmiths, the swamp lands of the Bagne offered new possibilities for work. Others with different training, attorneys and bankers, tried to find work in St. Laurent as clerks. The feared few, intellectuals and artists, who were branded as revolutionaries or traitors, ended up searching for work in the gold mines of the Amazon. The town of St. Laurent, however, couldn’t accommodate so many unemployed men. ‘The town’s folk used to throw stones, and rotten fruit at them’ recounts the daughter of a prominent council man in St. Laurent. ‘Many just slept in doorways and turned to drink’.

Today, St. Laurent is a forgotten border town on the Maroni river facing Suriname. Small wooden dug-outs shuttle back and forth across the muddy river laden with smuggled goods from the nearest trading post in Albina. Dutch goods are highly sought after in the town, especially cooking oil, diapers and cases of Heinecken beer.

After touring the islands with a handful of sea-sick French vacationers , I raced down the only highway in French Guiana from Cayenne to St. Laurent du Maroni in search of finding the last of the ‘bagnards’. St. Laurent had been home to many ex convicts, but no one could confirm if there were any still alive. I knew that if I could not find a survivor, I might, at least stumble across some good bricks. After asking around in my pigeon-french with the tourist office, the police and locals, I found myself at a dead end. I could not get a response to whether there were survivors of the Bagne, in this town. But then appeared Sparrow. A hefty sailor from Trinidad who sang calypso and spoke some English.

Sparrow took me at the hospital. A two story wooden edifice, built in the last century looming over the town, like an old shipyard in a Joseph Conrad novel. At the end of a long, dark corridor and flanked only by a wall of broken shutters, crouched an old man. His eyes fixed upon the floor boards, while mosquitoes swarmed overhead in the green, incandescent light. As the old man faded in and out of the night, the warden wandered, from room to room, checking in on the dying. At ninety eight, Mohammed Bashir has been an inmate at the St. Laurent de Maroni hospital for longer than he could remember. Deaf and senile, Bashir was sitting out his final days, just yards from the pier where he once disembarked, as a handsome young convict, from the steamship Le Marseillaise.

In 1924, Bashir, along with hundreds of thieves and crooks, was shipped from France’s port of Brest to this jungle outpost on the edge of the Amazon to serve a sentence resulting from a ‘family dispute’. He was the last known survivor of the colony of the damned. As he struggled to remember the names of his sons, his lips uttered some flash from the past. ‘There was some good’, he would mumble. ‘But a lot of bad’.

Upon his release in 1944, Bashir along with a other freed men, found jobs, got married and raised families in the same decaying town, only blocks away from the prison walls, which once housed them. Today, this weathered French Algerian spends his nights gazing out onto the banks of the Maroni river, where barges lie rusting in the weeds. As I leave the old man sitting alone in the desolate hospital of St. Laurent, I could not but help feel that Mohammed Bashir, was the last actor in a tragedy, which began over two hundred years ago, and is now finally drawing to an end. Like a cruel twist of fate, Bashir – a free man – was still a prisoner. A prisoner of time.

With the vision of the hospital and Bashir spinning in my mind, I strolled to the local watering hole to drench my thirst on a muggy night with a cold beer. It was then that the legend of Julia Channel came back to haunt me. ‘See the star of X’, advertised a poster which had been plastered on the bar’s window. ‘Xclusive engagement’ it screamed. It was a tempting proposition.

I had already seen Julia in her birthday suit by the pool and we ended up crossing part of the ocean together to our islands of health – the ile Royale. But there wasn’t much more to do in this tropical Klondike - crawling with smugglers and gold merchants - on a Saturday night, than go and see Julia again, swirling down a brass pole in her one act show at the Waikiki Club.

Sometime around midnight, St, Laurent was alive and kicking. Mopeds sped through the town while young men in gold chains honked at the mulatto girls standing in doorways in leopard-skin pants, plunging necklines and stilettos heels outside the club. Julia Channel must have really double-crossed someone to have ended up here,I thought. One can’t get much lower, on the porno totem pole than the Waikiki. But after debating the fourty dollar cover price at the door, I decided my money was better spent on baguettes and beer.

I don’t consider myself a collector of things, let alone a thief. But I had to do it. It was too tempting to give up and throw back into the ditch where it came from. But somewhere, someone I thought, might find this brick interesting enough to start a conversation. Or just appreciate it for all the trouble I went through trying to smuggle it out of the Bagne.

The brick in question, was not just any brick, except the fact it weighed a ton. It was a brick from a collapsed cell near to where ‘Papillon’ languished for years as one of the thousands of inmates at St. Laurent de Maroni detention camp. It was covered in layers of black mud, and abandoned since the last century when some prisoner probably threw it into a ditch on his way back to the Camp de Transportation - after toiling all day in the mosquito infested swamp - cutting down trees.

But there were many bricks. Most of them still supporting the colonial homes in St. Laurent de Maroni. Others so severely eroded by torrential rains, that they barely held up the garden walls of the old estates in this former colony. So why would anyone miss one ‘brique?’, I pondered to myself as I dug my knuckles deep into the mud, trying to pry loose this historical artifact.

Then suddenly, the only person in St. Laurent who had nothing better to do on a rainy Sunday morning than to keep an eye on bricks, stopped me in my tracks. “Monsieur, you cannot take this brique!’ stared down at me a cop in his blue uniform. ‘Why not?, I answered, pleading ignorance. “If everyone took a brick Monsieur, we wouldn’t have a town’ he scolded.

I managed to convince the Gendarme that I just wanted to take a picture of the brick, and that I would return it to the ditch first thing in morning. He smiled and left with a warning, ‘If you decide to take the brick from this town, you cannot not take it out of the country’, he warned. So as fast as I saw him disappear on his bicycle down the muddy street, the brick vanished into my knapsack, and there it stayed for two weeks.

As the day came to return home, I headed for the airport with my ‘brique’ wrapped neatly inside my clothes. As I recalled the words of the righteous copper in St. Laurent, I started having visions of a Midnight Express episode at the Air France counter. ‘Do you have anything to declare?’ asked airport security . ‘No. Nada. Rien’. I answered politely, digging my sweaty palms deep into my journalist’s vest. And brick smuggling is a heinous crime, I thought to myself –punishable by a US $ 2000.00 fine - as bricks fetch good money on the black market in Paris for antique collectors, a reliable scource told me. Bricks arriving in Paris from overseas flights are carted of to a warehouse and subsequently returned to this overseas territory as part of the historical repatriation program.

So I raced to the sign at the airport which spelled out the rules. ‘C’EST INTERDIT FIREARMS, DRUGS, FLAMMABLE LIQUIDS’. What about bricks?. Why wasn’t that on the list? . It must be a mistake, I thought to myself. And as I checked my baggage through to Caracas, my nerves began to crack. I swore the X-ray machine would find it and I would be carted off the plane to pay a heafty fine and face interrogation by the French grammar-police. Any square object that looks like well packed cocaine was suspicious. I was doomed to do more time in the Bagne.

Twenty minutes after the Airbus flight to Paris took off, we did too. I was a free man, like Charriere. The flight to Caracas seemed an eternity, so I dug myself in for a night of champagne, camembert and a warm blanket As I flew, my brick did too.

We touched down in Caracas at dawn, and much to my disgrace my luggage didn’t appear. My green backpack with my name and address on it was somewhere over the Atlantic or impounded in Cayenne by the French National Police. Air France hesitatingly took an inventory of all my personal belongings which had gone astray. Five boxers, three khaki pants, half a dozen cotton shirts and a guide book to the Guiane. ‘Anything else?’ asked the Air France lots baggage woman. “No nothing’, I replied thinking of my lost brick. Sure?. ‘Absolutement’ I replied in distress. So I headed home to my Bogota connection without any clothes and worst of all, my prized brick. Days of phonecalls and telexes between Caracas, Bogota, Paris and Cayenne passed without any sign of the luggage. Certainly, French Customs now had the brick firmly in their possession and were ready to auction it off or place it in a warehouse with hundreds of other wayward bricks.

Two weeks later, the phone rang at my home. It was Air France. ‘Señor Emblin, we believe you luggage is here’ said the airline offical. So I dashed out of the house -through Bogota’s drizzly streets - to El Dorado International airport. Sure enough, that green bag in the corner was mine, and almost unrecognizable by the bountiful red tape of French customs and a torn tags.

On a closing note, my brick went from Cayenne to Paris on the wrong flight, and on to Bangkok (someone at Air France confused Bangkok with Bogota). In Bangkok it was returned to Paris via Hong Kong, which seemed the fastest route. (It had all the United Airlines stickers). In Paris, Air France returned it to its point of origin Cayenne, as they thought I was from there. The brick went home again. But some rocket scientist in Rocambeau figured out that I had filled out the lost baggage form in Caracas, so it took off again to Caracas via Fort de France (Martinique). But in Caracas, the brick was too much of a problem, so they took the decision to return it to Paris on AF as they realized I could fill out a lost baggage form in Venezuela, but live next door. So, the brick was put on the next available flight to Colombia from Paris. Three entries into CDG (Charles de Gaulle) and no lost brick. “Your bag really flew” said Carlos, the baggage clerk in Bogota as he strained under the weight of the bag. ‘And my brick did too'.

Haggling with the concierge, I was told that the exhibionist was none other than the incredibly talented porn star known as Julia Channel. ‘It’s Julia. Le star du equis ’, whispered Francoise, as he arranged room keys at the reception. I had hardly touched down in this outpost of French colonialism in South America, and I was within striking distance of my introduction into the French film industry. Who needs Cannes I thought, when you can have Cayenne?.

It was evident from my arrival that French Guiane was an outpost for the misunderstood - rocket scientists, Legionnaires, a porn star on the literary trail of ‘Papillon’. I had watched back in my college days, many late night reruns of the movie ‘Papillon’ starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman, so I was drawn to French Guiane, not out of lust for Julia, but wanderlust. This small territory of France, wedged between Suriname in the west and the northeast shoulder of Brazil, is home to another breed of outcasts made famous in the movies - the French Foreign Legion.

From my home in Bogotá – Colombia - the trip involved three time zones, a night in Caracas, and a milk run of stopovers in the French Caribbean islands. When the Air France shuttle finally touched down at the Rochambeau Airport, -a gleaming terminal just outside the capital Cayenne - my travelling companion and I entered into shock. We could not believe that we were still in South America. Instead of the mud huts, we have grown accustomed to seeing from foggy aircraft windows, we had arrived at ‘de Gaulle’ of the Amazon.

And French Guiana is a department of France stubbornly resisting assimilation with the rest of the continent. At customs, a brusque grammar-Nazi scrutinized my faulty French pronunciation, but ignored my luggage. There are no roads to Brazil, but passengers fly direct to Paris on Air France. The currency is the French franc and the TV is beamed in from the Old World. The centrepiece of our hotel was a polished porcelain bidet.

After doing the tourist walk through Cayenne’s palm-lined Place des Palmistes, I faced the daunting prospect of finding souvenirs to take back home. I knew that once I left this tin roofed city in search of the abandoned prison camps, I would be as Papillon said ‘out in the middle of the swamp 1,000 miles from nowhere’. But the local shops sold mostly boxed butterflies- giant blue monarchs- and expensive French lingerie. I settled on a winged bug.

With my dictionary in one hand, and my endangered species in the other, I headed to the state museum to stock up on my general culture of the Guiane. The Caribbean-style mansion of painted wooden beams which housed the Museum seemed to be one of the few buildings in Cayenne which was not shuttered up on a rainy afternoon. After paying the entry fee of 20 francs, I wandered around giant jars of jaundiced formaldehyde with the preserved remains of snakes and floating toads. But on the second floor of the old Musee, a small cabinet caught my attention.

The cabinet formed part of an exhibition called- Les Briques du Bagne- the bricks of the ‘Bagne’. Three clay bricks, engraved with the letters A.P. stood on display. The bricks seemed somehow special and important to occupy such a privileged corner of the Museum. I had grown accustomed to museums all over South America which display canon balls and Simon Bolivar’s extensive collection of swords. But these bricks obviously played an important part as building blocks in this territory’s history.

In my faulty French, I asked the curator why the bricks?. He looked dumbfounded. I was the only tourist in three hundred years to take the effort of visiting the museum in Cayenne, and I was thrust into linguistic gridlock. I tried again. ‘Why the bricks?’. Why would a museum display three - one hundred year old - bricks?. ‘These are the bricks made by the prisoners of the Bagne’, came the reply.

WhenI stepped out of the museum, I was culturally enriched, but felt scolded. I had been in the Bagne all along. Bagne being the word used to describe this mosquito infested swamp and the land used by the old penal system operating across the territory. It was then that an awful thought crossed my mind. I must find a brick. Who needs a butterfly carcass when you can have a brick?. My motive was set, all I needed to do was find one.

In the eighteenth century, France was at war, fighting for control of her newly conquered territories in Canada and Louisiana from her arch-rival, the British. France also wanted to snag a piece of the colonial action in South America and in 1642 claimed the dense rainforest of the Guiane, as theirs. But serving no real economic purpose to Versailles, an edict was passed in 1791, converting the Guiane as a deportation centre for a cumbersome prison population who would subsequently died of yellow fever and malaria. As the French colonial experience in South America failed, another idea took root in France. Three tiny islands perched 40 kilometres from the Guianese shore were to become an experimental Alcatraz in the Atlantic.

This leafy cluster of islands, ironically called the Iles du Salud -Islands of Health- housed its first political prisoners back in 1792. But the exercise in convict deployment was short lived. Domestic problems at home forced the French Government to abandon the prisons and for decades the inmates languished on a forgotten shore. Following the successful deployment of criminals from England to Australia in the nineteenth century, France decided to follow example and populate the Guiane as one giant concentration camp.

A decree in 1852, set the process of mass deportations and common criminals were carted off to serve their sentences overseas in the sunny Caribbean. During the first couple of years some 8000 criminals were shipped here, but only 3000 survived. Poor hygiene and raging epidemics wrecked havoc on the inmates and the islands became identified with death and despair, instead of good health.

As the penal system grew, so did its reputation. It was impossible for convicts to escape from these islands, due to the shark infested waters, rough currents and treacherous cliffs of wind beaten rock. Soon these remote islands earned the nickname the ‘Devil’s Islands’, because they housed the most dangerous criminals of the Republic. In order to populate the islands, the French penal administration set up camps on the mainland and put petty criminals to work clearing the rainforest and cultivating the land. This system of work labour became known as ‘doublage’, or double- time. For every year, a prisoner spent locked up in confinement, he had to do an equal amount of time in the swampy ‘Bagne’ cutting down trees and cooking clay bricks to build more prison cells.

As France rushed to populate the Guyane, many prisoners were, in fact innocent of their crimes. Hasty trails and false accusations resulted in a series of scandals for the French government, in which respectable men were deported to this tropical inferno and left to die. Such was the case of Alfred Dreyfus, who became the cause célebre of the French intellectual classes and who insisted on his innocence, despite the fact that a military tribunal had accused Dreyfus of high treason for supposedly selling military secrets to the Prussian army. As a high ranking coronel in the French Army, Alfred Dreyfus was deported to Devil’s Island and spent four years and three months trying to get an appeal. It was only after the influential author and human rights crusader, Emile Zola wrote a dissertation titled ‘J’accuse’ in defence of Dreyfus that the French people realized the real motives behind Dreyfus’ arrest and exile.

The son of a Jewish family, Dreyfus had been framed by anti-Semites in the French establishment. Although Dreyfus regained his freedom in 1889, his military career was over and his reputation damaged beyond repair. Even today, a century after Dreyfus’ release, the so-called Dreyfus Affair continues to haunt the French political scene.

Although much of the infamy of the Devil’s islands is attributed to this famous political prisoner, the fate of others here is largely forgotten. Only one documented escape was pulled off my Charles de Rudio, who was dispached to the islands for his assasination attempt against Emperor Napoleon III of France. A plaque in the old warden’s residence, commemorates the legacy of the less fortunate inmates.

Today, the islands are an attraction for curiosity seekers from Europe who endure the hour’s boat ride from Cayenne. The forty kilometers trip could be easily done, if the sea is calm, but the crossing is at best of times, rough. Passengers are warned from the start to find seats inside the catamaran built for hurricane force winds. But I wanted to be out on desk, with the typical French honeymooners and of course, Julia in her white tank tee and Gucci glasses. Julia was on a sabbatical from the big screen. Too much porn, I guess can drive you to French Guiane.

Yet despite the waves, and being exposed to the best wet t-shirt contest of my life, Julia and I disembarked at the largest of the islands of the ile Royale. It’s funny what a hundred years can do to a place like Devils’ Island - a porn star and a photographer strolling down the concrete pier where once emaciated prisoners did.

The ile Royale, was the main penal colony, and housed most of the criminals, including Dreyfus and ‘Papillon’. Coconuts lie strewn across narrow foot paths, leading up a crumbling cemetery and down to a lighthouse tower and some abandoned barracks. After fifty years, nature has taken over some of the buildings transforming the cell blocks into eerie heaps of rubble and twisted steel. The solitary confinement cells still remain, but the roofs have caved in by erosion and the permanent pounding of hurricanes and tropical storms. But traces of penal life are strewn everywhere, literally. The wooden doors which once were slammed shut in the face of a convict, hang on their rusty hinges and one can count the scratches on a walls where a prisoner counted his days in darkness.

I climbed into an abandoned cell and closed the thick wooden door on myself. The shrill of the chicaras and the crying of black crows in the trees faded with the solitary confinement. The world around me fell silent. I was in what Charriere called the ‘mangeuse d’hommes’- the eater of men. Meanwhile Julia was strolling down by the sea - scouting for locations for her upcoming epic, and dipping her feet in the sea.

Convicted in Paris in 1931, at the age of twenty-five, for a murder he supposedly did not commit, Henri Charriere’s legend haunts Devil’s Island. Forty two days after his arrival in the French penal colony, Charriere became known as ‘Papillon’ because of the giant blue butterfly tattooed on his chest. He managed to escape, traveling some 1500 miles on the open sea in a tiny boat, but was recaptured by the French authorities and sentenced to two years in solitary. After seven more daring yet unsuccessful escapes, he was banished to Devil’s Island, in this archipelago of the damned. Finally, after languishing on the same island where Alfred Dreyfus pondered his fate, Papillon tried escaping one last time, by calculating the ebb and flow of tides, wind currents and the presence of sharks. The butterfly then floated to freedom on a raft made out of abandoned coconuts shells.

However most ‘bagnards’ – convicts - were not as lucky as Papillon. Prison terms handed down to the deportees were no less than ten years, and subsequently the convicts had to remain in French Guiana at least twenty. With the great influx of convicts, towns flourished and were administered entirely by the A.P.- the Administration Penitentiare. In St. Laurent de Maroni, an Indian community was displaced to make way room for a sprawling prison compound and the notorious Camp de Transportation. Here, prisoners who had survived the two week transatlantic crossing were processed and housed until their legal situation was defined. Most were banished to the islands, others were forced into chain gangs, clearing the forest and dying of hunger and infection. However, the most famous inmate of the Camp de Transportation has still not been released.

Locked in a wooden crate, in a building dilapidated by hanging vines and shrubs, the guillotine which once served the A.P, has been forgotten by the passing of time. Hundreds of men were executed in St. Laurent de Maroni, as a public display of terror and their cadavers thrown into the forest nearby. Execution by guillotine continued until the camp’s closure in 1936. For the prisoners who did not die by the blow of the blade, a lifetime in the bagne did not prove any better. The bagne became known as the ‘guillotine seche’ or dry guillotine, because it led to a slow, certain death in the tropics. Of the 70,000 convicts sent to French Guiana only 20,000 men survived.

Often, the prisoners who were swiftly executed by the guillotine, were considered the lucky ones. Being banished to the bagne, meant that, you lost touch with your family, and you could spend your entire life, going in and out of solitary confinement, sometimes not seeing the light of day, for years at a time. After being locked up in total darkness and isolation, the psychological scars ran deep. When the Salvation Army stepped in to help repatriate thousands of prisoners from 1946 to 1953, many men had no where to go. France begrudgingly had to received the bagnards, but French society did not.

By the time, a freed man returned home, there was often no trace of the life he once lived. Entire families had moved on or loved ones perished in the world wars which ravaged Europe during the ‘bagne’s’ existence. Some prisoners, after only having known the world inside the cold, damp walls of their cells, stayed on in the Guiane after liberation. Most notably, prisoners from France’s other colonies, Algeria and Morocco, who never really considered France as their home, found themselves spending their final days to this remote corner of the world.

For many ex convicts, the process of reintegrating back into society was as traumatic as the life they led behind bars. For the men who had been educated in France as skilled labourers, carpenters and blacksmiths, the swamp lands of the Bagne offered new possibilities for work. Others with different training, attorneys and bankers, tried to find work in St. Laurent as clerks. The feared few, intellectuals and artists, who were branded as revolutionaries or traitors, ended up searching for work in the gold mines of the Amazon. The town of St. Laurent, however, couldn’t accommodate so many unemployed men. ‘The town’s folk used to throw stones, and rotten fruit at them’ recounts the daughter of a prominent council man in St. Laurent. ‘Many just slept in doorways and turned to drink’.

Today, St. Laurent is a forgotten border town on the Maroni river facing Suriname. Small wooden dug-outs shuttle back and forth across the muddy river laden with smuggled goods from the nearest trading post in Albina. Dutch goods are highly sought after in the town, especially cooking oil, diapers and cases of Heinecken beer.

After touring the islands with a handful of sea-sick French vacationers , I raced down the only highway in French Guiana from Cayenne to St. Laurent du Maroni in search of finding the last of the ‘bagnards’. St. Laurent had been home to many ex convicts, but no one could confirm if there were any still alive. I knew that if I could not find a survivor, I might, at least stumble across some good bricks. After asking around in my pigeon-french with the tourist office, the police and locals, I found myself at a dead end. I could not get a response to whether there were survivors of the Bagne, in this town. But then appeared Sparrow. A hefty sailor from Trinidad who sang calypso and spoke some English.

Sparrow took me at the hospital. A two story wooden edifice, built in the last century looming over the town, like an old shipyard in a Joseph Conrad novel. At the end of a long, dark corridor and flanked only by a wall of broken shutters, crouched an old man. His eyes fixed upon the floor boards, while mosquitoes swarmed overhead in the green, incandescent light. As the old man faded in and out of the night, the warden wandered, from room to room, checking in on the dying. At ninety eight, Mohammed Bashir has been an inmate at the St. Laurent de Maroni hospital for longer than he could remember. Deaf and senile, Bashir was sitting out his final days, just yards from the pier where he once disembarked, as a handsome young convict, from the steamship Le Marseillaise.

In 1924, Bashir, along with hundreds of thieves and crooks, was shipped from France’s port of Brest to this jungle outpost on the edge of the Amazon to serve a sentence resulting from a ‘family dispute’. He was the last known survivor of the colony of the damned. As he struggled to remember the names of his sons, his lips uttered some flash from the past. ‘There was some good’, he would mumble. ‘But a lot of bad’.

Upon his release in 1944, Bashir along with a other freed men, found jobs, got married and raised families in the same decaying town, only blocks away from the prison walls, which once housed them. Today, this weathered French Algerian spends his nights gazing out onto the banks of the Maroni river, where barges lie rusting in the weeds. As I leave the old man sitting alone in the desolate hospital of St. Laurent, I could not but help feel that Mohammed Bashir, was the last actor in a tragedy, which began over two hundred years ago, and is now finally drawing to an end. Like a cruel twist of fate, Bashir – a free man – was still a prisoner. A prisoner of time.

With the vision of the hospital and Bashir spinning in my mind, I strolled to the local watering hole to drench my thirst on a muggy night with a cold beer. It was then that the legend of Julia Channel came back to haunt me. ‘See the star of X’, advertised a poster which had been plastered on the bar’s window. ‘Xclusive engagement’ it screamed. It was a tempting proposition.

I had already seen Julia in her birthday suit by the pool and we ended up crossing part of the ocean together to our islands of health – the ile Royale. But there wasn’t much more to do in this tropical Klondike - crawling with smugglers and gold merchants - on a Saturday night, than go and see Julia again, swirling down a brass pole in her one act show at the Waikiki Club.

Sometime around midnight, St, Laurent was alive and kicking. Mopeds sped through the town while young men in gold chains honked at the mulatto girls standing in doorways in leopard-skin pants, plunging necklines and stilettos heels outside the club. Julia Channel must have really double-crossed someone to have ended up here,I thought. One can’t get much lower, on the porno totem pole than the Waikiki. But after debating the fourty dollar cover price at the door, I decided my money was better spent on baguettes and beer.

I don’t consider myself a collector of things, let alone a thief. But I had to do it. It was too tempting to give up and throw back into the ditch where it came from. But somewhere, someone I thought, might find this brick interesting enough to start a conversation. Or just appreciate it for all the trouble I went through trying to smuggle it out of the Bagne.

The brick in question, was not just any brick, except the fact it weighed a ton. It was a brick from a collapsed cell near to where ‘Papillon’ languished for years as one of the thousands of inmates at St. Laurent de Maroni detention camp. It was covered in layers of black mud, and abandoned since the last century when some prisoner probably threw it into a ditch on his way back to the Camp de Transportation - after toiling all day in the mosquito infested swamp - cutting down trees.

But there were many bricks. Most of them still supporting the colonial homes in St. Laurent de Maroni. Others so severely eroded by torrential rains, that they barely held up the garden walls of the old estates in this former colony. So why would anyone miss one ‘brique?’, I pondered to myself as I dug my knuckles deep into the mud, trying to pry loose this historical artifact.

Then suddenly, the only person in St. Laurent who had nothing better to do on a rainy Sunday morning than to keep an eye on bricks, stopped me in my tracks. “Monsieur, you cannot take this brique!’ stared down at me a cop in his blue uniform. ‘Why not?, I answered, pleading ignorance. “If everyone took a brick Monsieur, we wouldn’t have a town’ he scolded.

I managed to convince the Gendarme that I just wanted to take a picture of the brick, and that I would return it to the ditch first thing in morning. He smiled and left with a warning, ‘If you decide to take the brick from this town, you cannot not take it out of the country’, he warned. So as fast as I saw him disappear on his bicycle down the muddy street, the brick vanished into my knapsack, and there it stayed for two weeks.

As the day came to return home, I headed for the airport with my ‘brique’ wrapped neatly inside my clothes. As I recalled the words of the righteous copper in St. Laurent, I started having visions of a Midnight Express episode at the Air France counter. ‘Do you have anything to declare?’ asked airport security . ‘No. Nada. Rien’. I answered politely, digging my sweaty palms deep into my journalist’s vest. And brick smuggling is a heinous crime, I thought to myself –punishable by a US $ 2000.00 fine - as bricks fetch good money on the black market in Paris for antique collectors, a reliable scource told me. Bricks arriving in Paris from overseas flights are carted of to a warehouse and subsequently returned to this overseas territory as part of the historical repatriation program.

So I raced to the sign at the airport which spelled out the rules. ‘C’EST INTERDIT FIREARMS, DRUGS, FLAMMABLE LIQUIDS’. What about bricks?. Why wasn’t that on the list? . It must be a mistake, I thought to myself. And as I checked my baggage through to Caracas, my nerves began to crack. I swore the X-ray machine would find it and I would be carted off the plane to pay a heafty fine and face interrogation by the French grammar-police. Any square object that looks like well packed cocaine was suspicious. I was doomed to do more time in the Bagne.

Twenty minutes after the Airbus flight to Paris took off, we did too. I was a free man, like Charriere. The flight to Caracas seemed an eternity, so I dug myself in for a night of champagne, camembert and a warm blanket As I flew, my brick did too.

We touched down in Caracas at dawn, and much to my disgrace my luggage didn’t appear. My green backpack with my name and address on it was somewhere over the Atlantic or impounded in Cayenne by the French National Police. Air France hesitatingly took an inventory of all my personal belongings which had gone astray. Five boxers, three khaki pants, half a dozen cotton shirts and a guide book to the Guiane. ‘Anything else?’ asked the Air France lots baggage woman. “No nothing’, I replied thinking of my lost brick. Sure?. ‘Absolutement’ I replied in distress. So I headed home to my Bogota connection without any clothes and worst of all, my prized brick. Days of phonecalls and telexes between Caracas, Bogota, Paris and Cayenne passed without any sign of the luggage. Certainly, French Customs now had the brick firmly in their possession and were ready to auction it off or place it in a warehouse with hundreds of other wayward bricks.

Two weeks later, the phone rang at my home. It was Air France. ‘Señor Emblin, we believe you luggage is here’ said the airline offical. So I dashed out of the house -through Bogota’s drizzly streets - to El Dorado International airport. Sure enough, that green bag in the corner was mine, and almost unrecognizable by the bountiful red tape of French customs and a torn tags.

On a closing note, my brick went from Cayenne to Paris on the wrong flight, and on to Bangkok (someone at Air France confused Bangkok with Bogota). In Bangkok it was returned to Paris via Hong Kong, which seemed the fastest route. (It had all the United Airlines stickers). In Paris, Air France returned it to its point of origin Cayenne, as they thought I was from there. The brick went home again. But some rocket scientist in Rocambeau figured out that I had filled out the lost baggage form in Caracas, so it took off again to Caracas via Fort de France (Martinique). But in Caracas, the brick was too much of a problem, so they took the decision to return it to Paris on AF as they realized I could fill out a lost baggage form in Venezuela, but live next door. So, the brick was put on the next available flight to Colombia from Paris. Three entries into CDG (Charles de Gaulle) and no lost brick. “Your bag really flew” said Carlos, the baggage clerk in Bogota as he strained under the weight of the bag. ‘And my brick did too'.

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

A message

Monday, June 12, 2006

Girl with pierced eyebrow.

Friday, June 09, 2006

To Sarah...

I am the last Edwardian,

I am the last of my kind

I have walked these fields for you

and held you near, dear

and now I drink my gin

in fear for tomorrow

I may not be here, and this

could be my final post to you,

as I look into your eyes

everyone around me

dies, in this is the darkest night of the year,

I sit down and write, before the fight

my final words of love

to you and I offer you my head

on a silver tray, like a man

I once knew,

who came to you

as John the Baptist.

and to whom I pray, so

I long to return to my sacred ground

to keep the most precious soul I have found,

so near, so remember this,

my dear, as I drink my gin in fear

that I have searched for you

among the distant shores,

the night crawlers and whores,

and I keep coming back

to your eternal smile

and I know, that this

my final sacrifice,

will not be in vain,

despite the wounds, the pain

in the rank and file, and maybe

there will be another time

for you and I, my dear,

a time to fly and not to die,

a time to love and not to cry,

so tomorrow as I stand,

at the gates of my Jerusalem,

I shall not let temptation have its way,

but rather I shall wait until the day,

when I see your face again on

London's tired streets,

with its beggars and sweets,

and I can hold you near

and drink my gin without fear.

-In the trench, 1917.-

I am the last Edwardian,

I am the last of my kind

I have walked these fields for you

and held you near, dear

and now I drink my gin

in fear for tomorrow

I may not be here, and this

could be my final post to you,

as I look into your eyes

everyone around me

dies, in this is the darkest night of the year,

I sit down and write, before the fight

my final words of love

to you and I offer you my head

on a silver tray, like a man

I once knew,

who came to you

as John the Baptist.

and to whom I pray, so

I long to return to my sacred ground

to keep the most precious soul I have found,

so near, so remember this,

my dear, as I drink my gin in fear

that I have searched for you

among the distant shores,

the night crawlers and whores,

and I keep coming back

to your eternal smile

and I know, that this

my final sacrifice,

will not be in vain,

despite the wounds, the pain

in the rank and file, and maybe

there will be another time

for you and I, my dear,

a time to fly and not to die,

a time to love and not to cry,

so tomorrow as I stand,

at the gates of my Jerusalem,

I shall not let temptation have its way,

but rather I shall wait until the day,

when I see your face again on

London's tired streets,

with its beggars and sweets,

and I can hold you near

and drink my gin without fear.

-In the trench, 1917.-

One day I will understand

how many words I abandoned

how many words I abandoned

in Montreal and how a bitter love

was sown on this, the street

I am walking still.

One day I will remember never to forget

how deeply

I loved you and how every kiss

I planted on your skin

would one day spring a tree on this

the street I am walking still

In the golden hour of a spent

generation, I held you in my arms

and beneath the Edwardian fixtures

and Chinese miniatures, I became man.

Maybe one day I will return to the street

I am walking still, to heal the wound

that cut so deep

and maybe one day

I will find more memories of you

on this the street, I am walking still.

Somewhere between Victoria Avenue and Saint Catherine Boulevard, Montréal. 1986.

was sown on this, the street

I am walking still.

One day I will remember never to forget

how deeply

I loved you and how every kiss

I planted on your skin

would one day spring a tree on this

the street I am walking still

In the golden hour of a spent

generation, I held you in my arms

and beneath the Edwardian fixtures

and Chinese miniatures, I became man.

Maybe one day I will return to the street

I am walking still, to heal the wound

that cut so deep

and maybe one day

I will find more memories of you

on this the street, I am walking still.

Somewhere between Victoria Avenue and Saint Catherine Boulevard, Montréal. 1986.

Thursday, June 08, 2006

Conversing with Islam

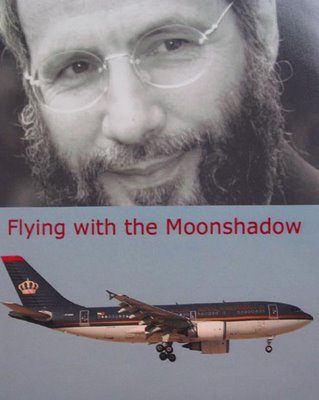

Flying with the Moonshadow, by Richard Emblin.

I have flown with Moon shadow. The author of it, Mr.Yusuf Islam, I mean, the artist formerly known as Cat Stevens. It happened several years ago and as I write this story, it seems as familiar to me now, as it was back then. It was December 1993 and I was about to leave India.

Now I know there are many people who have traveled with or sat next to important people on airplanes. This is not new. My brother shuttles between New York and Los Angeles, and has chatted to musicians and has had several champagne encounters with media moguls and highflying supermodels. But my encounter with Islam - Yusuf -to be precise, was in a strange way a religious experience.

Now for most people flying a religion don’t mix. There is nothing saintly about the treatment one receives these days from flight attendants, and airline food is quite, simply, ungodly. That’s if you are lucky to be given any at all. Flying like other aspects of our lives has become a chore. Something to do and be done with the least amount of resistance, and god forbid that the person next to you wants to start a conversation. In our age of global terror, too many people are striking up a lot more than just a conversation.

But when this story took place the WTC still stood and the islamic world was not at war. So, after three months exploring India, it was time to head home and face a grueling twenty-two hour flight back to Toronto, from New Delhi. My flight wasn’t the ‘red eye’ but a black-lung. After backpacking my way across the Indian subcontinent - and to avoid infections and other diseases, which are common to staying in negative five star hotels - I decided to smoke abundantly to kill the smells of India’s dirty streets. Smoking myself to death wasn’t really intentional, but I did and despite the fact that I had been vaccinated against virtually every known disease, I still managed to pick up malaria somewhere between Varanasi and Agra.

Smoking three packets of Goldflake cigarettes and finishing off with hand rolled cigars -biddies -did not help me, so I was forced to return home early to Toronto on a cheap ticket via Amman, Amsterdam and Montreal with a severe case of bronchitis.

Now in India everyone arrives and leaves the country before the crack of dawn - or should I say before ‘morning has broken’, in honour of my traveling companion Mr. Islam, who wrote a song back in 1971 with this title. We started boarding Royal Jordanian Airlines flight 193 to Amman, around four-thirty in the morning as a thick blanket of haze and smog engulfed Indira Ghandi International airport. The plane glowed like a firefly out on the tarmac and one by one we started looking for our assigned seats. I placed my camera bag into the overhead luggage bin, while others neatly stowed away their Persian prayer carpets.

At the front of the plane, the flight attendants boiled the breakfast tea and coffee. As I hoisted myself into a window seat, behind the wing, to catch my last Indian sunrise- a must when in India –I noticed a tall, bearded man staring at his boarding pass, wearing a small white headpiece, and dressed like a monk. He was the last passenger on the plane and precisely –as luck would have it - came and stood in the aisle, next to me. “Excuse me sir, is this seat taken?” he asked. I smiled and asked him, “What’s your number?” “24B” he replied. “Then this is it”.

As the final carpets found their resting place in the overhead compartments and the piped music of the Arab world’s greatest hits switched off, I realized that my traveling companion still hadn’t fastened his seatbelt. “May I help you with that” I asked pointing to the metal buckles of his belt. “Yes, thank you. That would be kind”, he answered as I pulled hard on the straps. And then we began to roll. The engines fanned up and the cabin lights dimmed as I pressed my nose to the window to have one last Indian moment and witness the great ball of fire rising in the east.

Poised at the end of the runway, my softly spoken traveling companion produced a rather large, leather bound book, from under the seat in front of him and grasped it firmly in his hands. Opening to page one, he began a humming to himself. Thinking that my bearded friend had had a head start with his morning prayers, I quickly blessed myself with the sign of the cross to give some leverage to my faith, and thought about the grueling eight hours which awaited me with the singing pilgrim. Little did I know that I had the window seat for the concert of my life.

“Aaaaaaalllaaaahhhh. Aaaaalllaaaaahhh’ began the chant on page one of the great book. Islam was in deep contemplation as we took off and climbed into clear skies. I tried to block out the droning of the engines by watching the Indian villages and farms fade from my view.

Then came the question. ‘Have you ever read the Qu’oran?’ asked my traveling companion, as we waited for the flight attendants in their smart, cranberry suits to serve us some hot tea and coffee. ‘No, I answered with sincerity. ‘I have not’. ‘It’s the greatest book of all’ came the reply.

Then the investigative journalist came out in me. ‘Where are you from Sir - I asked politely - as my friend had a pronounced English accent. ‘I am from England’ he responded sipping his breakfast tea. ‘And are you heading home?’. ‘No, I live in India’. ‘But I am heading to Boston to visit friends’. ‘How about you?’, he inquired. ‘I am heading to Toronto’ came my reply. ‘Must be nice and cold at this time of the year’. Let me remind you, as you read this story, that any conversation about Canada, always starts up and ends, with the weather.

We did small talk over the Arabian sea. But the conversation took a spiritual leap. I was in the final stages of life with malaria and Islam took pity on me. ‘Would you like to join me in singing a song?’ asked the passenger in the seat next to me. ‘Why not’, I replied, thinking that I could do with some divine intervention. Let’s start with the letter A. ‘A is for Allah' he said.

He opened the great book and warned me that one should never mention the supreme creator by name. So we hummed the letter ‘A’ for about 125 miles as we headed west on our silver bird. It was only several years later while researching the recording history of Yusuf Islam, that I came across a song recorded by the artist, called – believe it or not- ‘A is for Allah’. It’s part of a monumental children’s work with the same title - quite rare – and released a year after we met. I hope to this day that I -in some small way - helped take the song forward and contributed to its creation in this wild world in which we live.

My traveling companion had a beautiful voice. We talked of the Indian countryside and the goodness of its people, I told him about seeing the sunrise over the ganges and Tiger Mountain. He smiled and nodded. He had been there. ‘Yes, indeed it’s all beautiful’, he would say. And then the focus was on him. I asked him questions of growing up in London as a young man and New York in the 1970’s. Yet, I never could grasp his name. The Cat Stevens who sold 50 million albums and wrote ‘Peace Train’ and ‘The Wind’ was a simple traveling man by the name of Islam talking of England on a plane with a complete foreigner.

‘Would I know any albums of yours ?’ I asked. ‘Probably’ he replied, ‘I played folk music’. ‘If I looked for your music in a record store, what should I look for? I asked. ‘Yusuf Islam’, came he reply. It didn’t ring a bell. I had never heard of a pop star by that name. I knew of Dylan, Joni Mitchell, the Bee Gees and Clapton. But I had never of Islam.

Yet another interesting fragment of information about his former life surfaced as I realized that our eight hours were passing us by. ‘I lived in New York and was very close with Andy’ he said. Andy - I presumed was - Andy Warhol. ‘I used to go to these crazy parties with the Velvet underground’, he continued in remembrance of things past. ‘I did a lot of drugs. LSD’. ‘I drank a lot. There were many women’. ‘I was what you call successful’. I envied his story more than his success. ’But it was all an illusion’, he confessed.

‘It was while I was away from New York that I found a meaning to life’ he continued. I understood the feeling. ‘It happened one night. I was in an accident. I had been drinking a lot and doing drugs. I almost got killed and at the moment of coming face to face with my death, this beautiful word flashed before my eyes’. ‘It had golden letters’.

The answer for Stevens was in the word he saw. ‘The word that flashed before my eyes was written in a strange language’, he said. ‘I had never seen the word before. But when I awoke I realized that what it represented was the word for the unmentionable one’. ‘I decided then to give my life to him. G-D. The letter ‘A’. The unmentionable one. He became a Muslim.

His story moved me to tears. His words and the way he told it, were so impactful, that it didn’t matter anymore who this messenger was – or by what name he went. It was all in his message. It was about peace and humanity. He took an interest me and my view of Christianity and my mind-bending encounters with sacred cows. I was feeling better with Islam by my side. And Islam was a special man, a deeply spiritual individual, who found that conversing about G-d, the Canadian winters and India was more meaningful than the stories of his former life hanging-out with Andy, the creator of ‘pop art' or his gold records.

‘Remember’ - he said -‘it doesn’t matter to whom you pray’. The important thing in life is to believe. I agreed and we had become friends, heading west on the same flight path. ‘Jesus, Mohammed and Buddah are all sons of God’. It was during my own moment of personal despair – that I can truthfully say - Islam was there.

It was many years later, that I saw my traveling companion again. Almost a decade after we stepped out of the plane in Amman and shook hands and said our goodbyes under the midday sun in Jordan, I was in the frenzy of the post 9/11 story working as the Photo Editor for El Tiempo, Colombia’s national newspaper. I had been sorting through hundreds of photos which arrived every day on the wire services, when all of a sudden, AP posted pictures of a tall, well groomed man with a beard, standing in the middle of a frenzy of paparazzi at New York’s JFK international airport. The byline read something like ‘ …the artist known as Cat Stevens, Yusuf Islam, has been barred from entering the U.S on security grounds….’. I grabbed the computer screen and pulled it closer. I recognized him immediately. Cat was Islam, and my Islam was Cat.

I broke my silence with a quiet chuckle. I had my own personal story to tell of the man President Bush sees as a world threat. This same man had taken me to the edge of my faith and back, and I was still alive. Islam’s only ‘threat’ is that he is a symbol of hope and an unassuming titan of the music world. The man who strikes a conversation with you in Economy class, and not a match. Even though Islam has personally condemned the attacks of the Twin Towers, the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, this man of peace was a persona non-grata in the city that made Warhol, Dylan and above all, Cat Stevens.

British Prime Minster Tony Blair, personally invited Islam back home that night from New York. The pictures poured in. Yusuf, some eight hours later was back home on sacred ground -Heathrow airport - and received a warm welcome from the British people and of course, the paparazzi. I still clutch my UK passport to this day with pride after Tony took a leap of faith in the name of islam.

Now, not a day goes by when he isn’t there. I hear his songs on the radio and watch him receiving humanitarian awards on CNN -such as The Man of Peace prize. Rumour has it, Islam and Bono might be up for the Nobel peace prize. And as he prepares to launch a new album after years of silence this year - In the footsteps of Light- with the proceeds of the single ‘Indian Ocean’, going to the children victims of war and natural disasters, I re-live every second I spent traveling over another body of water – the Arabian sea - with the artist formerly known as Cat.

Saturday, June 03, 2006

the subway poems : I do not know

I do not know how many wars you conquered

or which medals recall that bitter day,

I do not know how many lovers left you

or those you let go astray.

I do not know the dreams that haunt you,

or if you find solace in the night,

I do not know the wounds you suffered

or if you ever had to fight.

I do not know the gods to whom to you pray,

or if candles were lit to bring you home,

I do not know if you ask forgiveness,

and seek shelter in this dome.

I do not know if my heart has made you cry,

of the pains you've had to bear,

what I know is that one bright day

I will be there among these sands of time.

written between Miami-London 1989

Friday, June 02, 2006

The Virgin of Taganga

A small fishing village on Colombia's northern coast - Taganga - is home to this beautiful Virgin Mary. I first set eyes on her many years ago, after an evening of drinking rum, smoking Colombian Gold and looking for the king, Elvis. I came back to her many years later when shooting a book project about the cult of the Virgin Mary in Colombia. She holds a special place in my heart, and may she help all you in this most uncertain world in which we live. She may not sing the blues, but she is the purest of blue.

A small fishing village on Colombia's northern coast - Taganga - is home to this beautiful Virgin Mary. I first set eyes on her many years ago, after an evening of drinking rum, smoking Colombian Gold and looking for the king, Elvis. I came back to her many years later when shooting a book project about the cult of the Virgin Mary in Colombia. She holds a special place in my heart, and may she help all you in this most uncertain world in which we live. She may not sing the blues, but she is the purest of blue.

Frontline : Colombia

The most dangerous street in Bogotá, used to be called The Cartucho, before they tore is down and built a park. The Cartucho was home to thousands of garbage recyclers, drug addicts and prostitutes. Here in the picture, one of the many inhabitants of this dead-end street, puffing away at his cigarette.

The most dangerous street in Bogotá, used to be called The Cartucho, before they tore is down and built a park. The Cartucho was home to thousands of garbage recyclers, drug addicts and prostitutes. Here in the picture, one of the many inhabitants of this dead-end street, puffing away at his cigarette.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)